|

TL;DRIn this post, I give a brief introduction to Stoicism and compare it to modern, watered-down versions of Stoicism, and, more broadly, other philosophies (or self-help methods) that are less demanding than Stoicism. I discuss why the strictness of Stoicism in its original form leads to relaxations that can often bear very little relationship to the original, and in some cases look almost the opposite of Stoicism. These relaxations can sometimes be troubling or dangerous because they allow Stoicism to be used propagandistically. |

Introduction to Stoicism

Not All Dead White Men has a good introduction to the basics of Stoicism. In my review of NADWM, I gave some brief hints about the doctrine of Stoicism, but I want to go into more detail here. To summarize the book’s overview of Stoicism, there are three major components to it:

(1) A belief that there is an absolute Good and Bad in the world and that the goal of life is to bring the world closer to the Good.

(2) A dictate that you (the Stoic) should not care about actions or events that are morally neutral: neither indicative of moral goodness nor moral badness. Example: your kid dying of a disease: assuming that you weren’t negligent, then you have not behaved badly. And there is nothing morally evil about a child dying before their parent — that is simply bad luck.

(3) A dictate that you (the Stoic) should not feel responsible for things that are not in your control even if that thing is morally good/evil. This includes other people’s morally good/bad actions. It also includes morally neutral but desirable things that may accrue to you that are outside of your control like reputation, societal standing, external rewards, friendship, etc. Insofar as those things happen because of your personal virtue, you should feel pride in the personal virtue that generated them rather than its downstream effects. And of course sometimes those things accrue to you in spite of personal vice, or are withheld from you even in the case of personal virtue, in which case you should not spend time happy at having them (because you have not demonstrated personal virtue) or sad at not having them (because you know yourself to have demonstrated personal virtue). In short, when societal reward comes apart from your morality, you should only care about your morality.

As you can tell, Stoicism is in theory quite a moralizing / social justice-y doctrine: all that matters is if something is right or wrong, and everything else is inconsequential. However, in practice, from what I can tell, a disproportionate amount of time spent by Stoics is actually on the morally neutral parts of life, namely getting people to try to see such morally neutral things are NOT worthy of emotion (tears, bitterness, etc.). It is ironic that this becomes a focus in Stoicism because the doctrine requires it NOT be a focus of one’s life. But presumably this irony happens because these morally neutral setbacks are the things people struggle most with bouncing back from, and Stoicism is sought out because it has the potential to help people with such problems. The “how to deal emotionally with my child dying” example I gave above is a very common Stoic problem because death during childhood was much more common than it is today — and no less tragic.

Another important feature of Stoicism is that it demands people morally critique themselves constantly but be forgiving of other people’s mistakes. Part of this is because Stoicism demands people not try to control things out of their control (component (3)) but part of it is just Stoicism’s humanistic belief that people do not do evil things because they are evil but because they do not know any better or how to be better.

When you take all these features together, Stoicism can be a very austere doctrine: it requires people to focus exclusively on morality, to kill emotions resulting from upsetting events that don’t stem from one’s personal moral failing, and to only critique one’s own moral failings and never anyone else’s.

That said, Stoicism isn’t without its own comforts. As I mentioned earlier, it tends to be sought out by people who are suffering personal tragedy so that they can recover from loss and setback. For this reason, Stoicism has a history of being particularly attractive to slaves and political prisoners: people who are forced to bear oppression or punishment that they know they did not deserve but which they are unable to prevent or escape from. What makes Stoicism attractive to people in these situations is that it vocalizes the conviction that life can heap as much unjust punishment as it likes on its victims but there is something dignified within that person that can never be touched or stolen from them or broken. This conviction is poignantly expressed in the poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley: “My head is bloody, but unbowed. […] I am the master of my fate. I am the captain of my soul.” In the view of Stoicism, losing, though it might feel humiliating, is actually a cheap, tawdry, unimportant event in life. Instead, your virtue, your decisions are the most important thing in the world, and they are something no one can touch.

These are the basics of Stoicism. As Not All Dead White Men outlines, because of the comforting aspects of Stoicism I outlined above, the philosophy is often peddled by modern proponents in a kind of bastardized “self-help” or “life hack” form. In some cases, these modern Stoics are sometimes so far from Stoicism that it prompts the question of how such a dramatic transformation can happen. For example, the book gives examples of people who lionize the Stoics while writing angry rants about how women’s selfish, illogical behavior “made” them bitter and callous. This is basically the opposite of Stoicism: it obsesses over behavior that is morally neutral (whether or not someone sleeps with you); it obsesses over other people’s actions/morality (a no-no in Stoicism); and when the adherent’s personal morality finally comes into the picture, the person openly, brazenly admits to becoming a worse human being (whereas personal virtue is the only thing Stoics believed a person should feel personally responsible for and should actively cultivate at every opportunity)!

In the rest of this post, I’ll talk about this self-help version of Stoicism as well as other relaxations of Stoicism and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses.

Stoicism and self-help

As I said earlier, Stoicism can be quite austere. The first relaxation that people often instinctively apply is to replace the Stoic requirement to serve the world’s Good via your actions with the intuitive notion of “good” where it means “good for me”. In other words, social justice (serving The Good) becomes self-help (living a good, happy, fulfilled life). A major piece of Stoicism (the moralizing) has been lost. But it is very easy/tempting to make this leap because there are already many prominent self-help-like aspects to Stoicism such as its advice for dealing with loss, which seems to be advice for how to be happier in the face of tragedy, as well as its tips for cultivating personal virtue, which seems to overlap with advice on self-improvement.

While this self-help form of Stoicism is easier for the adherent to live up to, the downside is that it replaces morality with self-interest. Most times, morality and self-interest align or at least do not conflict. (Is the world worse for a person being happier? Probably not. In fact, all things equal, it’s probably a better world — so saith a utilitarian, at least.) In the cases where morality and self-interest do conflict, however, to prioritize self-interest is to embrace an amoral view of the world.1

Stoicism and Red Pill

The feature of Stoicism that I think is the most difficult to live up to is the dictate that you should criticize and tightly control the actions of yourself, while declining to judge or take control of other people’s actions. This asymmetry in how a Stoic should react to themselves vs. how they should react to others is cognitively hard on people — I think people instinctively tend toward either the rule of treating other people the same way you treat yourself (the Golden Rule, or universalism), or if they tend toward asymmetry, it is in the direction of hypocriticality (imposing lower standards on one’s own behavior and criticizing others more harshly). Stoicism, on the other hand, demands hypercriticality as the normative way of being in the world — holding oneself up to a standard that you MUST hold no one else to.

It is, therefore, understandable that many adherents of Stoicism swap out hypercriticality with either universality or hypocriticality. However, this relaxation combines badly with the first relaxation (the replacement of the moral good with the personal good). If you’re practicing Stoicism only to improve your own standing, and you spend significant time criticizing other people and trying to change their behavior, you basically become the opposite of a Stoic — a self-interested annoying person. When this happens, there is very little left in the original Stoicism other than perhaps the self-help “life hacks” of improving one’s resilience to failure and setback (which is, after all, compatible with ruthless self-interest).

Stoicism and Confucianism

Stoicism in its original form is very similar to Confucianism. Both doctrines believe in the existence of the Good, and that the purpose of life is to serve this Good. They are moralizing doctrines. However, unlike Stoicism, the practice of morally criticizing other people (remonstration) is a key component to Confucianism. In other words, it engages in the second relaxation (asymmetry) but not the first (morality). Insofar as there is asymmetry to how moral critique should be applied in Confucianism, it is not a self/other asymmetry but rather that remonstration should always “punch up” rather than down. In other words, the power of a person determines how much they should be subjected to criticism with the emperor at the top largely needing to fulfill the Stoic ideal (always criticizing oneself and taking responsibility for one’s actions but not blaming the peasant or the brigand for their actions and rather helping them be better). Of course, frequent self-critique is important to being a good person as well and Mengzi recommends that, whenever you see someone lacking in a virtue, you should turn that criticism inwards and determine whether, in fact, you have been remiss in displaying that virtue.

Confucianism also somewhat relaxes along the morality dimension by considering a larger set of things people do and care about to be part of the moral domain. For example, the death of loved ones is something Stoicism considers morally neutral and so says experiencing sadness is the result of not understanding the world properly. By contrast, in Confucianism, it is morally good to value one’s family, and so morally proper to experience sadness when they die. In other words, grieving actually embodies personal virtue. This moral relaxation is similar to nonviolent communication, which I consider next.

Stoicism and nonviolent communication

Oh hey it’s been too long since I talked about nonviolent communication on my blog. Like Stoicism, a major insight/assumption that NVC relies on is the notion that no one can ever make anyone do anything. Just like your will is beyond other people’s control, so it is that other people’s actions are beyond your control. You can pressure people into behaving how you want them to behave by making it costly to disobey, but at the end of the day, they might still choose those costs over complying and you have utterly failed to control them. In Stoicism and NVC alike, realizing this can come as a mental balm to people who struggle to control other people and end up only experiencing failure and disappointment. NVC and Stoicism teach people to give up on these delusions of control and thus find peace through detachment and the renunciation of expectation.

As I discussed in this post, giving up on controlling other people has the effect of creating an asymmetrical burden where the practitioner of NVC must hold themselves to much higher standards of behavior than they do the people they interact with. They must not only choose to communicate in NVC, but must also choose to put the effort into “listening” in NVC to people who, unlike them, are not using it. That said, nonviolent communication advocates applying the same communication and understanding towards yourself as you do others, so while you should not criticize people for being worse at NVC than you are, there are still some universal characteristics to the way NVC can/should be applied. This makes it less rigid than Stoicism while preserving some of the hypercritical aspects of it.

In addition, NVC is also less demanding than Stoicism because it allows people to feel, verbalize, and focus on emotions that are the result of things that are not the result of Moral Good or Moral Evil being done in the world. In the case of NVC, the emotions come from personal needs and values including ones that have moral dimensions and others that don’t. Unlike Stoicism, which labels feelings stemming from (unmet) needs/values that aren’t moral in nature as being “false impressions”, NVC acknowledges these feelings as valid and encourages people to verbalize the needs/values that are generating those feelings. In other words, NVC features the first relaxation (morality) and relaxes somewhat in the second aspect (asymmetry) but not fully. In this regard, it is very similar to self-help, which is not surprising as it is largely a self-help technique.

In general, NVC is strict about how one is allowed to communicate but fairly flexible regarding the ends to which people apply that communication. As a result, NVC can be used for social justice purposes or self-help purposes; used to criticize oneself or criticize others; used to cultivate one’s personal virtue or better meet one’s needs. Stoicism allows the first in each pair to be pursued but not the second.

Overall, I like NVC the best because I think it is (like Confucianism) accepting of people’s need to grieve, while also (like Stoicism) it urges people to give up on trying to coercively control other people, instead encouraging people to persuade through verbal appeal. When used empathetically, I think NVC can actually be even more effective at furthering social justice causes than Stoicism, despite having less of a laser focus on social justice. The reason why is because I think underlying many cases of injustice is deprivation of needs, and NVC allows people to voice and raise awareness of that kind of deprivation even when it happens to you, rather than viewing it to be out of your control (when it happens to you) and therefore sidelining it the way Stoicism does. Even though NVC can seem amoral at times, the feature it has of tying emotions to understandable, universal needs/values that must be explicitly stated aloud (i.e. must be publicly accountable) subtly imposes a kind of universalist morality on the practice.

Summary

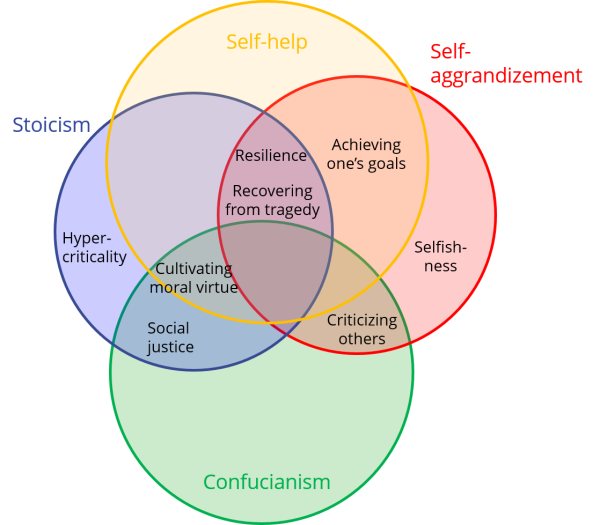

The following figure summarizes the difference between the forms of Stoicism I talked about (original Stoicism, self-help Stoicism, and self-aggrandizing Stoicism (the form that can be found in the Red Pill world)), as well as Confucianism. Nonviolent communication is so flexible that, as far as I can tell, it can be used for every purpose in the diagram, so imagine a big circle around everything labeled “NVC”.

Stoicism is a very admirable doctrine in many ways and its practices can bring some peace and mental wellness to its practitioners. However, it is also one of the most demanding practices in ways that, if one is not careful, allows bastardized versions of Stoicism to easily spread and get more uptake than the original form of Stoicism, which is more austere and therefore much more difficult to consistently practice. Relax Stoicism too much and it becomes self-aggrandizement, almost the opposite of Stoicism, only sharing with it the tips for being resilient in the face of setback.

↑ 1 My usual caveat that amorality is just an unpopular form of morality applies.

(1) A belief that there is an absolute Good and Bad in the world and that the goal of life is to bring the world closer to the Good.

You fell at the first hurdle there my friend.

There is no good and evil in the world, only in our intentions.

(2) A dictate that you (the Stoic) should not care about actions or events that are morally neutral: neither indicative of moral goodness nor moral badness.

You should care deeply, however how you cash out your compassion is where your morality lies.

(3) A dictate that you (the Stoic) should not feel responsible for things that are not in your control even if that thing is morally good/evil. This includes other people’s morally good/bad actions.

You are responsible inosfor as you can act to prevent the bad actions of others, or to prevent them from happening.

There are no dictates, just appeals to good reason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“There is no good and evil in the world, only in our intentions.” I’m not an expert on Stoicism, but I don’t think this is the typical doctrine of Stoicism. In Stoicism, there are many things that suggest that good and evil exist in the world external to people’s intentions. For example, there is the idea of sages (people who act correctly all the time); there is a spiritual notion of Reason / Logos that orders the world; there are virtues that Stoics view as everyone’s calling to cultivate (wisdom, courage, justice, temperance). All of these things suggest that there IS an external definition of virtue that Stoics must compare themselves to and live up to (i.e. perfection and absolute good and evil exist theoretically in the world outside of people’s actions).

“You are responsible inosfor as you can act to prevent the bad actions of others, or to prevent them from happening.” This seems like a bit of a complicated issue for Stoicism. You are responsible for your actions but I don’t think a Stoic would say you’re responsible for failing to prevent something from happening, because actions external to you are out of your control. It’s unclear to me how much action Stoicism believes people to be obligated to take in order to try to prevent something bad from happening (is it permissible to use violence or the threat of violence to prevent someone from killing someone, for example?), but it’s clear that Stoicism denies that there is any clear link between what you do and how people respond (i.e. preventing someone from doing bad is not something you have the ability to do, so from your point of view, other people’s actions cannot reflect morally on you).

LikeLike

“There is no good and evil in the world, only in our intentions.” I’m not an expert on Stoicism, but I don’t think this is the typical doctrine of Stoicism”

It is a fundamental assumption in Stoicism. We can work it from first principles from Socrates if you like, but metaphysically there is no possible idea of “malign forces” in Stoicism. There is no moving away from this position without destroying the whole philosophy.

The only “evil” is what people do, and people do evil because they are ignorant “of the good” as Socrates put it. They are in error.

“Just as a target is not set up in order to be missed, so neither does the nature of evil exist in the world.

Epictetus Enchiridion 27.

The sage is a hypothetical paragon of a wise person, and what characterizes a wise person is that they know and understand the world.

The idea of “the Good” in this sense is someone who has the good sense, the intelligence and the wherewithal to act as they ought to act in any circumstance. Virtue means excellence. A good knife has the virtue of “sharpness”, This doesn’t mean that there are entities of “sharpness” and “dullness” that exist in the world independently of knives, any more than there are essences of “knowing” and “ignorance” in the world.

The Stoic cardinal virtues are all forms of knowledge.

1. Prudence is knowledge of which things are good, bad, and neither; or “appropriate acts”.

2. Temperance is knowledge of which things are to be chosen, avoided, and neither; or stable human impulses”.

3. Justice is the knowledge of the distribution of proper value to each person; or fair “distributions”.

4. Courage is knowledge of what is terrible, what is not terrible, and what is neither; or “standing firm”.

Goodness is virtue, and virtue is knowledge, the right kind of knowledge applied appropriately.

Badness is ignorance…it has no existence beyond our assumptions, judgments and choices.

Logos is not a spiritual force, the Stoics had no idea of anything “spiritual” in that sense, everything is physical governed by cause and effect. Logos describes that everything that exists is tied together in a regular causal network, that can be observed, measured, and understood.

Reason, rationality comes from ratio, which is how things relate to one another in a very real sense.

“4:45.What follows coheres with what went before. Not like a random catalogue whose order is imposed upon it arbitrarily, but logically connected. And just as what exists is ordered and harmonious, what comes into being betrays an order too. Not a mere sequence, but an astonishing concordance”

Marcus Aurelius: Meditations 4:45.

“You are responsible inosfor as you can act to prevent the bad actions of others, or to prevent them from happening.”

Absolutely central.

“You are responsible for your actions but I don’t think a Stoic would say you’re responsible for failing to prevent something from happening,”

You are indeed. 100%

To witness injustice and do nothing is to be guilty of that injustice. If you see a little old lady being robbed, and you do nothing, you may as well have robbed her yourself. If a child was drowning two feet from you, do you think it is ok to watch them drown because “it’s not in your control”?

Making the decision to save the child is in your control. What you decide is where good and evil are. If you are prepared to watch the child die, you need to say why, and it better be good.

Other people’s actions do not reflect on your morally, but how you react to their actions is the essence of your morality.

There are, on the other hand, two kinds of injustice—the one, on the part of those who inflict wrong, the other on the part of those who, when they can, do not shield from wrong those upon whom it is being inflicted.

“For he who, under the influence of anger or some other passion, wrongfully assaults another seems, as it were, to be laying violent hands upon a comrade; but he who does not prevent or oppose wrong, if he can, is just as guilty of wrong as if he deserted his parents or his friends or his country”

Cicero De Officiis.

A Stoic is proactive seeking to do good, to do service to the greater good, the harmony of the whole.

You participate in a society by your existence. Then participate in its life through your actions—all your actions. Any action not directed toward a social end (directly or indirectly) is a disturbance to your life, an obstacle to wholeness, a source of dissension:

Marcus Aurelius Meditations.

No school has more goodness and gentleness; none has more love for human beings, nor more attention to the common good. The goal which it assigns to us is to be useful, to help others, and to take care, not only of ourselves, but of everyone in general and of each one in particular.

Seneca, On Clemency 3.3

LikeLike

Excellent article. So is non verbal communication the best moral to apply for one self?

How should we choose our morals? This is a very deep and interesting topic indeed.

One could say one adheres to utilitarianism, but in practice sometimes it isn’t that easy. Life doesn’t tend to be black and white, and yet, morals do see things in black and white…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not sure how to choose our morals. For me, I find the moral system I use (based on the Golden Rule) quite easy/intuitive/obvious to adopt, but others may disagree.

Note: nonviolent communication isn’t quite a moral system — it’s more a technique that encourages people to practice empathy (towards themselves and others) and to render explicit the stakes of a conversation (morals / values / needs that are at play), for the purpose of making communication more effective. That said, I think it does in the end embody a kind of moral system based on empathy, which I think is strongly connected to the Golden Rule and morals based on egalitarianism/fairness and reducing hurt/harm. This is quite similar to the morality I subscribe to, which is based on empathy, equality, and not hurting people.

Utilitarianism has some similarities to NVC and the Golden Rule, because it too sees all life as having equal value (egalitarianism) and important to promote happiness and prevent pain (hurt/harm). I see utilitarianism as close to/related to my morality system.

LikeLike